- Tel: +86 813 2105845

- Fax: +86 813 2105845

- Mob: +86 13778532392

- Contact: Mr. Jacky

info@dinosaurs-world.com

info@dinosaurs-world.com Jackydinosworld@gmail.com

Jackydinosworld@gmail.com Jackyyiming@gmail.com

Jackyyiming@gmail.com Jackyzengdinosaursworld

Jackyzengdinosaursworld

- What do you call a gigantic lizard no human will ever see?

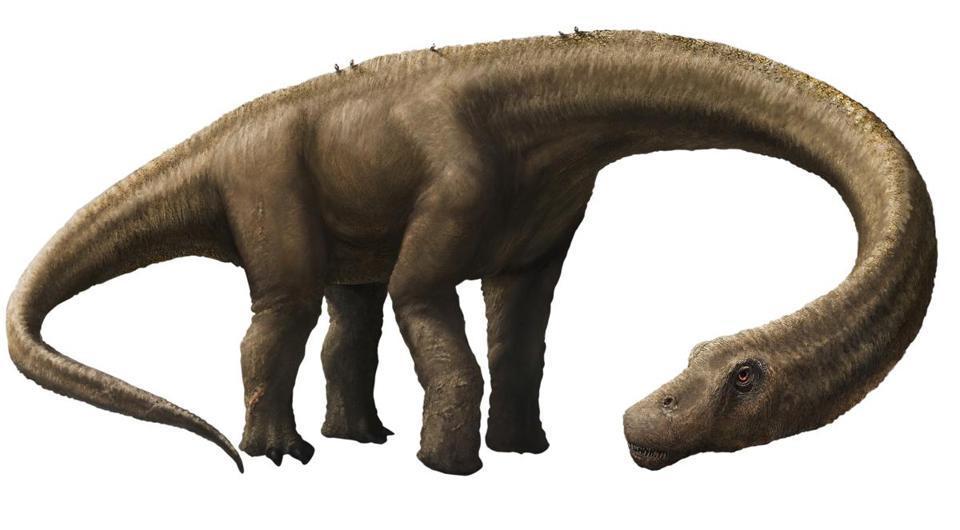

When paleontologists announced earlier this month that a mostly complete skeleton of a new species of giant sauropod dinosaur had been discovered in southwestern Patagonia, it was immediately clear that many things about this beast were awesome. According to scientists, the animal, which lived on the planet about 77 million years ago, would have been 85 feet long, with a 37-foot-long neck. It would have weighed 65 tons and was still growing at the time of its death, making it the largest-known land animal ever.

When paleontologists announced earlier this month that a mostly complete skeleton of a new species of giant sauropod dinosaur had been discovered in southwestern Patagonia, it was immediately clear that many things about this beast were awesome. According to scientists, the animal, which lived on the planet about 77 million years ago, would have been 85 feet long, with a 37-foot-long neck. It would have weighed 65 tons and was still growing at the time of its death, making it the largest-known land animal ever.

But among all the awesome details about the sauropod, one of the awesomest was a human touch: its name, Dreadnoughtus schrani. The dreadnought was a turn-of-the-last-century battleship, while “schrani” pays tribute to entrepreneur Adam Schran, who helped finance the research. As Slate blogger Ben Mathis-Lilley wrote, “DREADNOUGHTUS....You don’t have to write it with all capital letters, but it’s recommended.”The scientists who named Dreadnoughtus were building on a longstanding tradition of dinosaur names that emphasize massiveness, fearsomeness, or general ability to inspire awe, from Tyrannosaurus Rex (“tyrant lizard king”) to more recent inventions like Diabloceratops (“devil-horned face”) or Anzu, named after a Sumerian winged demon. Dinosaur names have a poetry that transcends any taxonomic requirement: The names must convey the wonder that scientists feel toward these monumental, vanished beasts—and in turn capture the imaginations of kids, museum-goers, and potential donors.

The rules for classifying any new species, dating back to Carl Linnaeus’s 18th-century binomial conventions, are technically simple. Animals get a genus and species name (in our case, for example, homo is the genus and sapiens the species) often based on Latin or Classical Greek roots, which must be unique. In the 19th century, when a fossil-hunting competition arose between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, naming became a weapon of scientific one-upmanship as well. Cope, for instance, named a dinosaur Laelaps aquilunguis (Laelaps is a mythical Greek hunting dog; “aquilunguis” derives from Latin words for “eagle-clawed”) in 1866. In 1877, it turned out that Laelaps was already being used to describe a bug, and Marsh triumphantly changed the genus name to Dryptosaurus, or “tearing lizard” in Greek. Marsh’s names, including Apatosaurus, Triceratops, and Stegosaurus, won out “in the majority of cases,” said Peter Dodson, a paleontologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

But when Henry Fairfield Osborn, then-president of the American Museum of Natural History, named a giant new predatory dinosaur “Tyrannosaurus rex” in 1905, he was trying to do something a little different. Osborn, said Dodson, was an ambitious promoter of his new fossil halls, sending scientists to the American West and Mongolia and mounting skeletons in lifelike poses. “[Osborn] really wanted people in the museum,” Dodson said. “He wanted to impress people with the vigor of paleontology,” and a vigorous name was one way to do that.

Today, a more global approach to science has shifted names away from the old Greek and Latin naming tradition. Some new names borrow from languages spoken where a discovery was made. Leinkupal laticauda, another Argentine sauropod announced in May, derives its genus name from words in the indigenous Mapudungun language for “vanishing” and “family”; the animal was the last extant species of the Diplodocidae family. Others, now that Chinese paleontology has become increasingly dominant, add the Mandarin word for “dragon,” “long,” to a place name. Qiupalong henanensis, named in 2011, means “Qiupa Formation dragon from Henan Province.”

But the most thrilling names remain, no doubt, the bombastic, Osborn-style ones: Khaan (from the Mongolian for “lord”); Sauroniops (“Eye of Sauron,” a Lord of the Rings reference); Raptorex (“robber king”). Playful naming isn’t unique to paleontology, of course: There are insects named after Angelina Jolie and Hitler, a Central American wasp named Heerz lukenatcha, the Colon rectum fungus beetle. However, paleontologists do confront unique issues that may encourage exciting names. One is funding. Since the 19th century, private backing has been crucial to expeditions and discoveries. A name that attracts press and museum visitors, or even one that namechecks a donor, as with “schrani,” can help ensure that a paleontologist gets to make more discoveries in the future.

More generally, dinosaur names describe a being most people can’t even imagine meeting. The name has to work sort of like the children’s-book-style illustrations that paleontologists commission to accompany their scientific papers, turning a heap of bones into something vivid.

That brings us back to Dreadnoughtus. When Kenneth Lacovara, the Drexel University paleontologist who first discovered the dinosaur, was looking for a name, he had a very specific image in mind. “As opposed to being hapless dimwitted platters of meat in the landscape, as [sauropods are] portrayed a lot of the time, I wanted to portray Dreadnoughtus as this badass animal that deserves a lot of respect,” he said. But he also wanted a name that would get people excited, especially kids, who often come to science for the first time through dinosaurs. He made a list of 30 names, including Umbra titan (“shadow giant”) and Sylvana Titan (“forest giant”), and market-tested them on everyone who came over to his house. Dreadnoughtus—from the steam-powered, big-gunned mainstay of the early 20th-century British Royal Navy, a boat with nothing to fear, exactly like Lacovara’s dinosaur—was the “runaway winner.”

A great name, Lacovara said, is just one way to start connecting people to crucially important broader ideas. Through his research, he said, “I can help people link themselves to our ancient past, I can help people understand themselves within the context of evolution and geological time, and maybe help people just go outside and realize how lucky they are to live on such an amazing planet. And we’re not going to be able to provide that if we keep this stuff to ourselves.”

2014-09-29

2014-09-29

New dinosaur species help scientists fill in evolutionary gaps

New dinosaur species help scientists fill in evolutionary gaps Feathered everything: just how many dinosaurs had feathers?

Feathered everything: just how many dinosaurs had feathers? Dinosaur Fossil With Fleshy Rooster's Comb Is First of Its Kind

Dinosaur Fossil With Fleshy Rooster's Comb Is First of Its Kind Scientists finally decode how dinosaurs turned into birds and learned how to fly

Scientists finally decode how dinosaurs turned into birds and learned how to fly Dark matter may have killed the dinosaurs, claims scientist

Dark matter may have killed the dinosaurs, claims scientist New duck-billed dinosaur uncovered in Alaska, researchers say

New duck-billed dinosaur uncovered in Alaska, researchers say

- Contact Us

- Tel: +86 813 2105845

- Fax: +86 813 2105845

- Contact: Mr. Jacky

info@dinosaurs-world.com

info@dinosaurs-world.com Jackydinosworld@gmail.com

Jackydinosworld@gmail.com Jackyyiming@gmail.com

Jackyyiming@gmail.com Jackyzengdinosaursworld

Jackyzengdinosaursworld

- Copyright @ 2009 - 2020 Zigong Dinosaurs World Science & Technology Co.,Ltd.